Blood pressure measurement is one of the most common medical tests performed across both physician’s offices and hospitals worldwide. Ensuring the accuracy and reliability of this measurement is critical for the proper diagnosis and treatment of millions of patients. Yet, measuring blood pressure is a procedure that is also highly prone to error.

In this article, we’ll discuss why we so often get blood pressure readings wrong and the most common mistakes that cause false highs and lows. We’ll also lay out simple tips you can use to avoid these mistakes, master this fundamental skill in patient care.

Lack of ongoing training

Inaccuracy in blood pressure measurement has persisted across the healthcare spectrum, despite extensive education and efforts to raise awareness of the negative consequences these faulting readings can bring.

One issue experts believe may be at the center of this issue is a lack of ongoing training in proper blood pressure measurement techniques.

In fact, according to a joint survey of over 2,000 healthcare professionals by the American Medical Association and American Hospital Association (AMA-AHA), retraining in how to succeed in accurate blood pressure measurement is not nearly as common as it should be.

Specifically, the survey found that1:

- Approximately 50% of physicians and physician assistant report receiving no additional blood pressure retraining after graduation.

- A full one-third of nurses in addition to approximately a quarter of medical assistants received no retraining.

Clearly, despite the importance of accuracy in blood pressure measurement, we still have far to go in supporting healthcare professionals in the development of this skill.

Common blood pressure mistakes

Regardless of your position, whether you are a physician, nurse or other healthcare provider, there are five common mistakes that can lead to blood pressure inaccuracies2,3. These are:

- Wrong cuff size

- Cuff positioning

- Patient preparation

- Incorrect patient positioning

- Talking

Accuracy of cuff size

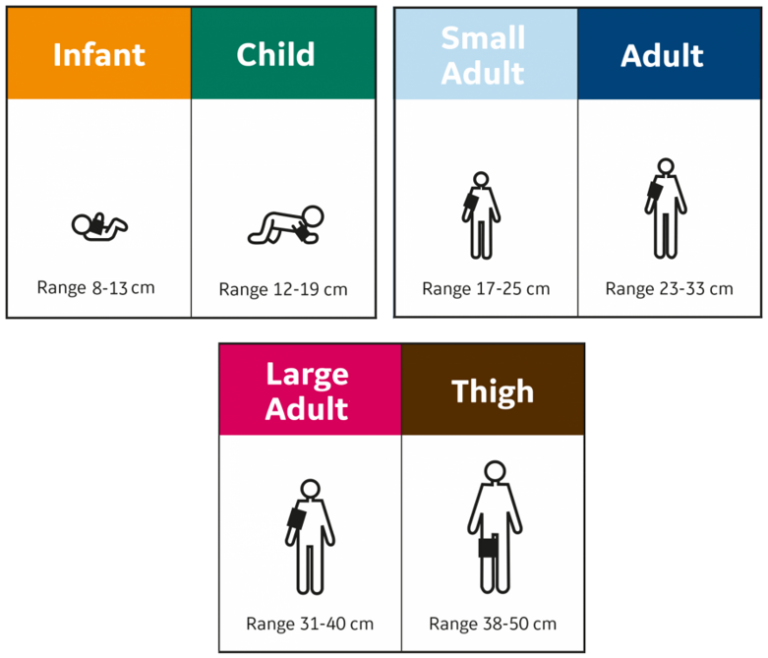

Choosing the wrong-size blood pressure cuff can affect accuracy by up to 30 mmHg4. The American Heart Association recommends a cuff bladder width of 40% of the arm circumference and a cuff bladder length of 80% of the arm circumference5.

To ensure accuracy of sizing, begin by measuring the patient’s mid upper arm circumference in centimeters. Next, use the sizing chart below to determine which cuff size should be used based on that measurement. (If the patient’s cm measurement is between sizes, choose the larger cuff if width is appropriate.

Remember when choosing the cuff size, that if the inflatable portion of the cuff is too narrow or the cuff is too loose or uneven, a false high can result. On the other hand, a cuff that is too wide may result in a false low.

Cuff positioning

Proper cuff positioning also plays an important role in blood pressure measurement. The cuff should always be placed on a bare arm. As wrapping the cuff over clothing can add five to 50 points to your reading1.

Next, place the artery mark located on the cuff over the patient’s brachial artery. Wrap the cuff snugly and securely, allowing space for two fingers to fit between patient and cuff.

Insufficient patient preparation

Properly preparing the patient is also necessary to achieve the most accurate blood pressure readings. Whenever possible, ask the patient to empty their bladder prior to taking a reading since having a full bladder can raise a blood pressure measurement by 10 to 15 points1.

Incorrect patient positioning

Accurate blood pressure measurement also relies on the position of the patient. Having feet or back poorly supported may falsely increase a reading by six to 10 points, while sitting with legs crossed my raise pressure by two to eight points1. When sitting back should be supported, legs should be uncrossed and feet should be placed flat on floor or stool.

Perhaps the most common mistake in blood pressure measurement is allowing patients to sit or lie with their arms hanging by their side, since when the upper arm is below the level of the right atrium, the readings will be too high. If the arm is unsupported and held up by the patient, pressure will be even higher2. When sitting, arm should be positioned with measurement cuff level with the heart1. If patient is supine, a pillow should be placed beneath the arm to elevate it to heart level.

Talking during measurement

Patients should also refrain from answering questions and talking on the phone during a blood pressure reading as even active listening can raise your measurement by 10 points1. Patients should remain still and silent to ensure an accurate measurement.

Improving patient care and safety through accurate blood pressure measurement

Blood pressure measurement is vital to making accurate, timely decisions in healthcare. However, common mistakes can derail blood pressure reliability and compromise patient care and safety. Following the steps above including choosing the correct cuff size and positioning, improving patient preparation and positioning and asking the patient to refrain from talking during measurement can dramatically improve accuracy and reliability, so that you can provide your patients with the care they deserve.

References

1: Adderton, J., and Lynda Lampert. “AMA Looks to Retrain Doctors on Taking Blood Pressures.” All Nurses, 26 November 2019, https://allnurses.com/ama-looks-retrain-doctors-taking-t711288/. Accessed 21 November 2021.

2: American Family Physician, and Liz Smith. “New AHA Recommendations for Blood Pressure Measurement.” American Family Physician, 1 October 2005, https://www.aafp.org/afp/2005/1001/p1391.html. Accessed 7 December 2021.

3: “Blood pressure measurement mistakes can lead to misdiagnoses.” Medical Xpress, 9 May 2018, https://medicalxpress.com/news/2018-05-blood-pressure-misdiagnoses.html. Accessed 7 December 2021.

4: Manning, D.M., et al. Miscuffing: Inappropriate blood pressure cuff application. Circulation 68(4), 763-6 (1983).

5: Pickering, T., et al. Recommendations for Blood Pressure Measurement in Humans: An AHA Scientific Statement from the Council on High Blood Pressure Research Professional and Public Education Subcommittee. Hypertension 45, 142-161 (2005).